Light the flaming torches and stand back: Are you a good leader of your social media mob?

I’m pulling together my yearly online journalism ethics lecture. It’s the fifth-ish lecture on this module (some previous ones online) and the fast-moving nature of this stuff means I’m really starting from scratch but I always go back to previous ones to see where my thinking was.

A prevailing theme for me has been how the ethical standard is set and who sets it. The online landscape clearly stretches moral and ethical concerns and the question for me has always been about how much of that we take on board, how much we take on the norms of the web, and how much is a more fundamental journalism ethic that we should stand by.

In questioning that in my lectures over the years, what I’ve noticed is that the tone of online journalism has changed. It’s divesting itself of some of the tradition and reveling in the norms of the medium. Ethics is on the move and the volume has gone up.

So this year my general starting point for the lecture is that outrage is the new journalism.

Outrage is nothing new for online journalism (and it’s not a new observation). Take comment sections on news sites. They are great examples of *outrage creation – *baiting readers with a story you know is going to get comments regardless of the tone of the comments.

Take this example from the Daily Express about the apparent calls to move a grave because of it’s proximity to a Muslim grave. Skip to the comments and revel in the outrage. By a strict reading of any rendering of a professional journalism ethic, it seems pretty hard to defend.

The argument about who is responsible for the comments on a site is well-worn. Comment systems work within resources and the law. Despite efforts by some publications to curb offensive behavior, the idea that the publication or the journalist take any responsibility for eliciting these comments in the first place seems moot. Even if they are providing the target, the damage is done by those who pull the trigger – the people who comment.

This form of outrage creation is also now common in social media. A casual tweet or post – * ‘you won’t believe what this person just said’* – and a viral hit and loads of links later most walk away. But not everyone.

Increasingly I’m seeing a different form of outrage creation. It’s not the fire-and-forget of an article and it’s comments, it’s sustained, crowd-sourced, journalist as brand-outrage. It’s I’m outraged and I want you to share that outrage . Literally share it. Retweet, hashtag and join me in confronting the source of my outrage.

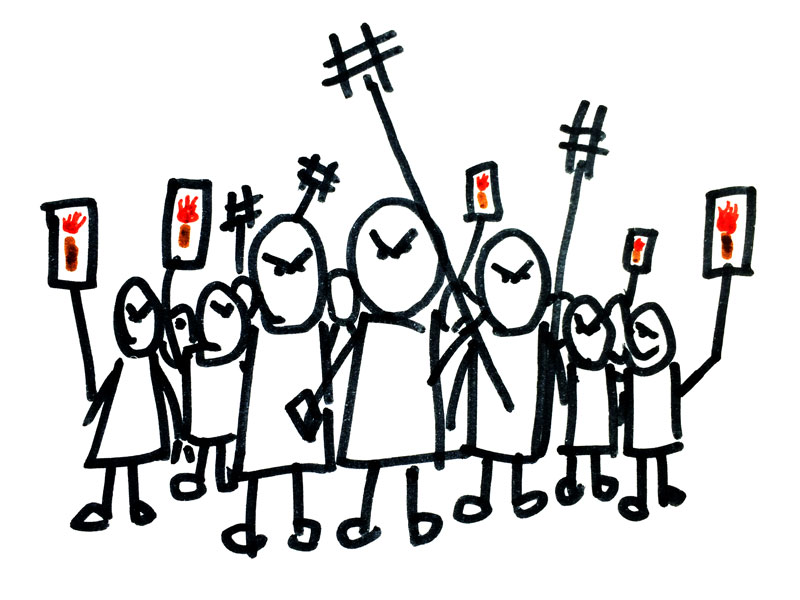

We can tell ourselves that this is simply engaging with an audience. This is the power of social media to right wrongs. It may be. But by another name it’s an angry mob. It may be hashtag shaped pitchforks and flaming torch apps but it’s a mob and it’s your influence (often affiliation with a recognisable journalism brand) and audience (a healthy follower count) that they gather round.

In the social media world its easy to see follower counts as a gauge of popularity. Like audience figures or circulation counts. It’s easy to forget that they are individuals with the capacity to reach out and touch. Perhaps that’s why it can take journalists by surprise when they turn on you. Still, it can be deceptivly easy to distance yourself from the activities of your audience – they aren’t friends, You don’t follow them; a useful degree of separation.

So when someone posts something vile on social media or trolls another user using a link to your work or a hashtag you’ve promoted, its easy to fall back on the same rhetoric that’s used for commenting on web sites. You might make the ammunition but you don’t fire the gun.

What’s the difference? Is someone who goes on to troll a target of your outrage any less of a responsibility than a commenter on your website? Remember this is ethics not law.

I would argue that whilst the comments on a website help create and feed a mob (with all the issues that can create for a site) what you post on social media means you create and lead a mob.

Social media mobs have done some great things but ethically, are you doing the right thing by and with yours?

Notes:

* – I know by citing the Daily Express I’m not doing myself any favours. It’s easy to write them, and the commentors, off as some kind of nutjob fringe. Sadly they are journalism. For the sake of this post the visibility and tone served a purpose. I’m sure that journalists from sites with more active moderation (and more generally agreeable politics) would testify to no less offensive and distressing material appearing on their virtual doorstep. *

* – I tried really hard not to push the gun/arms metaphor here but forced to I’d have to say that I don’t think journalists on social media are like gun or ammunition manufacturers, even though the logic of distance against blame makes for some very similar ethical positions. For what it’s worth I think a lot of journalistic use of social media is more like the activities of the National Rifle Association. *